Fear is necessary for keeping us alive.

Unfortunately, because humans live in a very metaphorical and symbol-based reality (using 'sophisticated grunting' as language, and words as symbols), our fear system can sometimes make us act as though our life is in danger, when it's not.

That's when we might want to ask ourselves if we want fear to block us from doing something, or if we should let ourselves feel afraid, but decide to act anyway.

Here are 3 key things to know about

why fear plays such a part in our life and how it affects us.

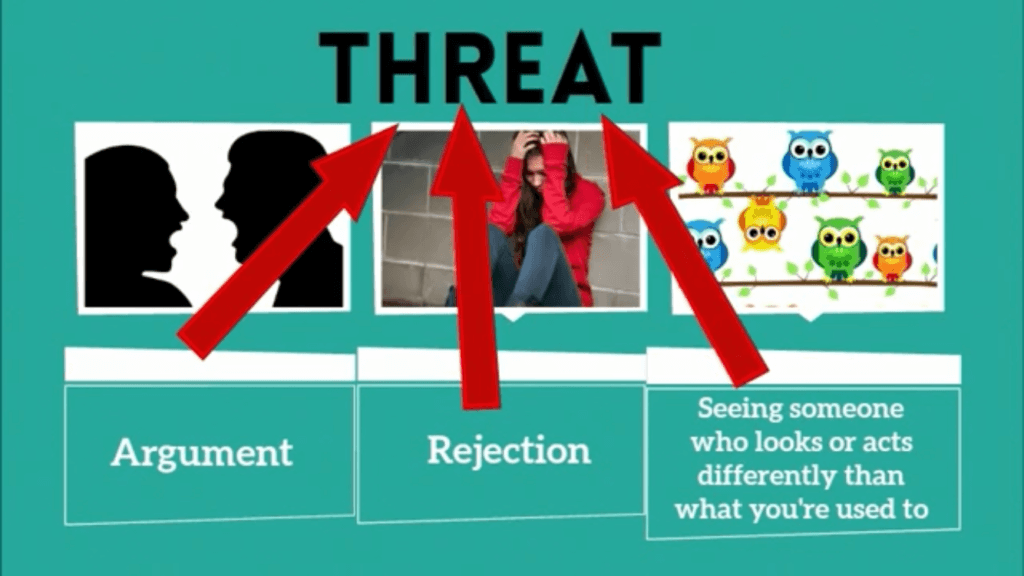

#1: Fear is generally the default reaction to something our mind-brain-body perceives that we can’t control or that we can’t understand.

This is because we have a higher chance of surviving if we detect 'false positives' rather than false negatives.

Another way to say this is that when our system automatically puts something unfamiliar in the 'danger' category, if it's correct - great! That just saved our lives.

If it's wrong, 'oh well' - we might miss out on something that could be beneficial, but the cost of our system assuming the worst is worth it because it keeps us alive (technically speaking, from a brain-based statistics perspective).

This means that there is a higher chance that most of us miss out on new experiences because our mind-brain-body system places things we don't understand into the 'threat' category.

Some of the things we miss out on can include:

- meeting people who are very different than us

- listening deeply to try to understand opinions that are different than what we hear all the time

- allowing ourselves to feel feelings that we don’t understand

- having an experience that could change our life, even if it could end up in rejection (like public speaking, auditioning for something)

If we don’t build a track record of experiencing these kinds of things,

our system doesn’t have any new ‘data’ to predict the probability of surviving those experiences.

So we end up just ‘sticking to what we know’.

The more we interact only with people and situations we are familiar with (including online), the bigger and more generic the category of ‘danger’ becomes.

The world becomes binary: a small number of familiar people are ‘safe’ and the massive amounts of unfamiliar people and experiences are ‘unsafe’.

This makes the world a very stressful place!

The mind-brain-body needs data.

It’s that simple.

The brain-body system needs lots and lots of variety in its data.

When it doesn’t get that, all it can do is generalize.

As we saw earlier, it will place anything unknown into its giant threat category.

It has to do this, from a survival perspective.

# 2: We tend to over-generalize fear

Because our mind-brain-body system is an efficiency machine, it also does us the "favour" of grouping things together so we don't have to analyze each and every person and situation.

If we've had one negative experience with something, many neural resources are devoted to making sure we don't repeat whatever that was.

This can happen for things like getting food poisoning from eating oysters and never wanting to eat them again even though each oyster is not necessarily going to give us food poisoning.

This can also happen for things like if we experienced a parent or caregiver as threatening, our brain may pick up on something from a boss, or romantic partner and associate whatever that is with our past negative experiences and then put us into a defensive mode without us even realizing it. (This is often called a 'schema').

And this can happen when we dislike the opinion of one person.

Our brain will try to be efficient by putting that person into a category, so we can just avoid (or attack) that category altogether.

From a brain- perspective, over-generalizing** is much more efficient than actually trying to understand and getting to know every single person we interact with.

**In fact, some of Carol Dweck's original research was on the use of 'generic language': as children, around 40% of the language we get about the world is 'generic', meaning pluralized and categorized, rather than individuated. Example, "cats are ___, adults are ____". This can lead a child to believe certain traits are innate about a group, rather than see them as individuals. (see Navigating the Social World for more on this).

#3 We ‘learn fear’ from other people.

This means we don’t even need to have a direct experience with something to be afraid of it.

We just need to be around someone else who is afraid of it (especially if we trust that person). Their reaction will create biofeedback signals that we then detect and associate with whatever they are afraid of.

(An example of this would be a child being afraid of a bee or spider even though they’ve never been hurt by one.)

What do all three points have in common?

They show us that:

Many of us are afraid and defensive more often than we realize.

How do we get around this?

We need to become more familiar* with unfamiliar things, people, and perspectives.

But since there’s a good chance that our mind-brain-body is ensuring that we avoid new behaviors and unfamiliar experiences, we need to consciously override this system.

Fear is extremely easy to learn and extremely difficult to unlearn.

We can’t expect ourselves to ‘unlearn fear’ naturally.

We will never 'get out' of our built-in survival mechanisms, and we don't really want to. They are there for a reason.

But we can train features of the brain to come online more quickly in response to our fears so that if whatever it is ' doesn't kill us, it makes us stronger'.

Here’s one way to train your brain to have more access to its higher order features:

Beware of your 'fastest reaction'.

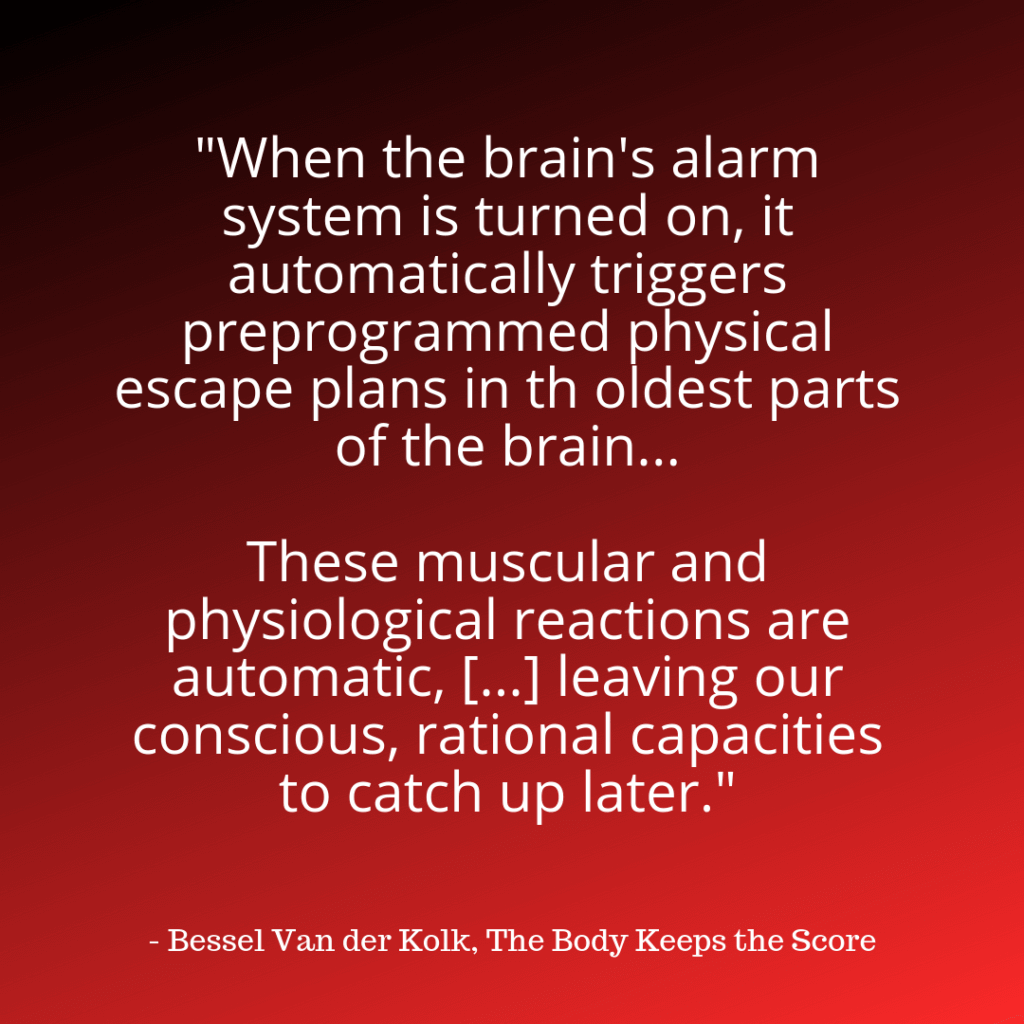

Your survival mechanisms will always be the first to take over.

Signals coming from our five senses and our internal organs need to travel from our spinal cord, brainstem, limbic system, until they finally reach the areas furthest away from our spinal cord - the prefrontal cortex. This means that signals take longer to reach the more evolved areas of our brain.

The prefrontal cortex is slower-to-respond than our more primitive reflexes.

The prefrontal cortex plays a major role in being the ‘control tower’ of the brain. It has a lot of coordinating and processing to do. It is designed for more complex functions and calculations, rather than reflexes.

Your 'fastest' reaction will keep you alive when something is an actual threat.

You want to jump out of the way of a moving car without calculating, without thinking about 'why is the car going so fast?'.

So let's be grateful that we have automatic reflexes that help us move our hand off a hot stove before we realize it's hot.

BUT... for ‘non-life-threatening’ situations, such as conversations, online behavior… situations where our life is not actually in danger... it may be worth honoring the micro-moments it takes for our more thoughtful brain features to catch up.

When you are engaging in an angry text or phone conversation:

the faster you are replying, the less likely this is coming from your more evolved neural architecture.

The more you are able to slow the pace down, take some breaths, the more you are giving your higher order brain a chance to keep up, process, and then come up with something that is more intelligent than a repetition of primal fear-based 'grunting'.

Bottom line: if you’re feeling like you have similar negative reactions to someone or something over and over again, and it’s not a dangerous situation, see if you can slow down your reaction.

Take a moment before you move a muscle (this includes speaking and texting!) to let more signals travel to your higher order brain areas.

As always, breathing deeply and slowly allows more oxygen to come in, and is an automatic trigger to your system that it’s not a life-threatening situation.

Breathing deeply also engages the vagus nerve,which can dampen the sympathetic nervous system (flight flight mode), and open up blood flow to neural resources related to communication and flexible problem-solving.

If you’re not that ‘familiar’ with your breath, do whatever you can to notice it more. (this is huge for building circuitry in the prefrontal cortex, which can help you have more intentional control over your behaviors).

Some other ideas to try to help your mind-brain-body system become more open and flexible:

- Expose yourself to areas of knowledge you don’t understand.

- Learn how to notice your breath even when you are stressed or upset.

- And most of all, create a track record for yourself of trying new things and surviving them - even if they don’t go well.

If we keep having the same arguments with the same people, it means we are ‘re-acting’*.

We will keep acting out the same dramas until we break the cycle.

This same idea relates to us collectively as a species.

If we don't want to see history continue to repeat itself, we have to override our own default defense systems.

It starts on an individual level first.

*notes on vocabulary:

Brain: I prefer using mind-brain-body instead of ‘brain’ because it is a complex system that includes the electromagnetic fields surrounding and pulsing through the body + feedback loops carrying intelligence from cells (especially the cellular membranes), visceral organs (especially the heart) to the brain and from the brain back to the organs and muscles + a ‘social mind’ that includes the data created by signals we exchange with others. If I do use ‘brain’, I mean the mind-brain-body system.

Familiar: its origin includes 'belonging to a family', which I love: when we attempt to get to know someone or something, we are making them ‘familiar’. We are making them a part of our family.

Reaction: to re-act. To act again and again in the same way.