Humans are the most experience-dependent species that has ever existed on the planet.

Our brain depends on its experiences to build itself.

Our genes lay a blueprint, but they actually only contain a microscopic amount of information

compared with the trillions of connections and bits of information

that end up actually building and shaping the human brain.

Let me give you an example.

- Close your left eye and hold your left index finger a few inches from your nose.

- Take your right index finger and hold it directly behind your left finger, a couple inches away.

- Make sure you center the fingers so you can only see your left one.

- Now switch having only one eye open at a time.

- You should see your fingers in different positions.

What’s happening is each eye is seeing a completely different view of the world,

but our brain fuses the images together to help us make sense of our reality, to see in 3D, have depth perception, and know that an object is hidden behind another.

This is called ‘stereoscopic vision’, or binocularity.

The thing is, as babies, we are not born with stereoscopic vision.

Like many features of our brain, it is ‘experience-dependent’.

This may sound like an inconvenience.. Wouldn’t it be easier if we were just born being able to see in 3D?

Possibly, but the fact that our brain waits to see what’s in store for us first - before it figures all of that out -

is a major reason why we are as adaptive and flexible as we are.

The fact that we are so experience-dependent means

that our brains will customize us for our very specific circumstances.

But there is also a less helpful side to having such an experience-dependent brain...

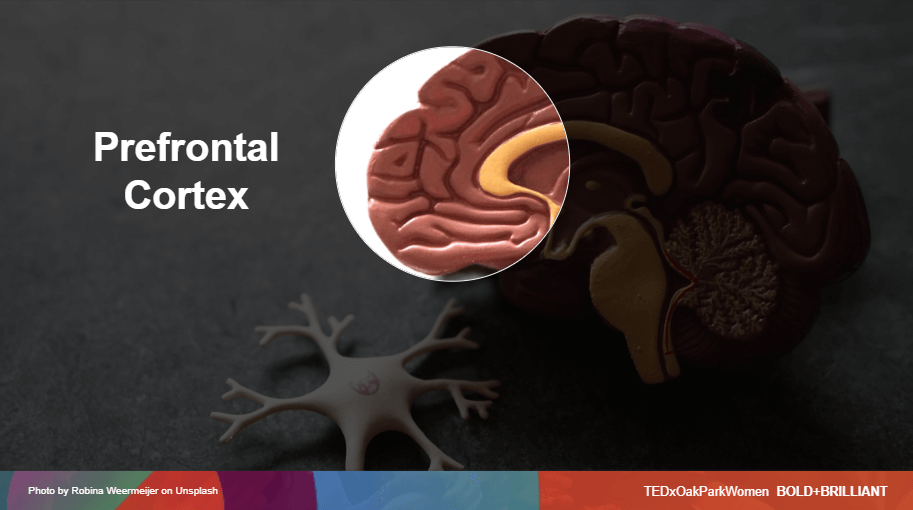

Part of this has to do with the frontal areas of our brain, especially something called the prefrontal cortex. This area is related to something called executive functioning. Many of you have likely heard of executive functioning - these are the skills related to controlling our impulses, thinking of future consequences and weighing of pros and cons among other things.

The prefrontal areas also help us with self-regulating, with managing our stress levels and how our emotions affect us. Without those prefrontal features, we become ‘dysregulated’,

we become volatile in the storm of sensations and stimuli that bombard our senses at every moment.

Examples of dysregulation include throwing a tantrum, over-reacting to the smallest thing,

or collapsing in the face of a challenge.

The thing is, as babies, we are not born with those self-regulating or executive functioning skills.

We are only born with the potential to develop them and we need our experiences to help us do that.

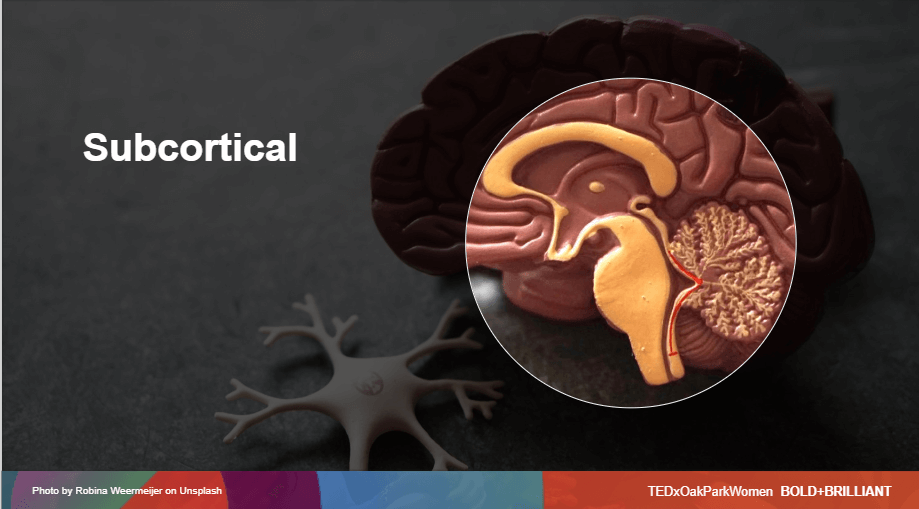

In fact, some scientists would say that when we are born, we are ‘subcortical’,

meaning that we don't have particularly high speed access to the features of the cortex

- and especially the prefrontal cortex.

Instead, our brain basically ‘triages’ what circuitry it should focus on first.

Because, sure, it would be great to have impulse control

but if we can't even stand upright or move our hand to our mouth,

those skills need to be taken care of first.

So the brain devotes its resources in waves, over time.

And it focuses first on the cortical areas towards the back of the brain

- the areas that take care of movement and coordination, for example.

The frontal areas, especially that prefrontal cortex, are the last to fully come online.

This means that when we are little,

we do not have access to brain features that can help us self-regulate.

To deal with this, our brain does something very clever:

it basically ‘outsources’ its executive functioning and emotion regulation to our caregivers.

Our caregivers act as stand-in for our prefrontal cortex.

That means we need the people around us to be ‘prefrontal cortex models’.

I call them "PFC models".

We need them to be able to regulate their emotions, manager their stress and control their impulses,

in order to help us build those features in our brain.

Our earliest years are when this is most important, but our experiences shape these brain features for many years.

In fact, brain mapping indicates that the prefrontal areas are only fully developed in our mid twenties.

So, as humans, we actually need ‘pfc models’ around us for a huge portion of our life

in order to develop our self-regulating abilities.

This means is that our past is playing a major role in how we react to life now.

If we did not have consistent ‘pfc models’ in our life - people who knew how to deal with their own emotions and control their impulses - there’s a good chance we may have some challenges in doing that for ourselves.

So does this mean we are pretty much all doomed?

Well, the beautiful part of having an ‘experience-dependent’ brain, is that...

The experiences we give it now, can still have an impact.

We can give our brain new experiences that activate more of our brain,

and especially those prefrontal areas.

The more we do, the stronger those areas become.

Our brain can change.

We can do this in a bottom-up way and a top-down way.

A bottom up way is to have new experiences that challenge us.

Things like speaking in public, having conversations with people we don’t agree with,

experiencing new cultures, and learning things we’ve never learned before.

If we feel nervous about those things, that’s actually great news for your brain because

feeling nervous about a challenge and then taking action requires you to regulate your own emotional distress.

We can also activate new circuitry in those prefrontal areas in a top-down way

by having a new awareness about ourselves.

When we notice our own reactions, and pay attention to sensations in our body when we are getting upset,

we are activating our pfc.

When we take time to slow down instead of reacting immediately to something someone has said,

we are working out our executive functioning skills.

When we control an urge to turn to screens or social media when we are bored or stressed,

and instead go for a walk or take some long exhalations -

we are strengthening the self-regulation networks in our brain.

Having an experience-dependent brain means that although our past plays a big role in how we see things now,

it ALSO means we can choose new experiences that build new circuits.

We don’t have to keep repeating our past over and over again.

But we need to make this a priority.

Because as a species, we are at a crossroads.

There are so many young people in this world who are surrounded by parents, caregivers, teachers and leaders

who themselves are dysregulated and who did not have their own pfc models.

This means that a massive portion of the planet is completely dysregulated.

When we don’t know how to self-regulate, because no one is around to show us,

we turn to devices or substances to do this, or we repeat our past behaviors over and over again

because we are stuck feeling overwhelmed by the world, our relationships and our own emotions.

We also dysregulate the people around us and especially the next generation

because their brains depend on our prefrontal abilities in order to help them self-regulate.

It’s clear that our brain depends on our experiences.

So what can you do with this?

This first thing is to acknowledge that your past plays a role in how you react to things now.

You are human, so there’s no way around this.

Second, because you - along with all humans - have an experience-dependent brain,

you can choose new behaviors now that not only create new circuits for your brain to work with,

but that serve as a model for other human brains to develop their circuitry.

And finally, because you have an experience-dependent brain,

your very personalized, customized, unique experiences

have built neural networks in you that have never existed before and will never exist in anyone else ever again.

No brain will ever be like yours.

It’s up to you to share your unique neural circuitry with others.

It’s your choice of which brain model you will be: one that is stuck because of its past experiences, or one that is a model to help others have new experiences that build and shape their unique and powerful brain.

References:

Aoki, C., & Siekevitz, P. (1988). Plasticity and brain development. Scientific American, 259, 56-58.

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss. Vol. 1: Attachment. New York: Basic Books.

Diamond, S., Balvin, R. & Diamond, F. (1963). Inhibition and choice. New York: Harper & Row.

Gogtay et. al., (2004). Dynamic mapping of human cortical development during childhood through early adulthood, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 101.

Harvard Center on the Developing Child: developingchild.harvard.edu

Hensch TK. (2005). Critical period plasticity in local cortical circuits. Nat Rev Neurosci.,6:877–888.

Jando et al, (2012). Early-onset binocularity in preterm infants reveals experience-dependent visual development in humans, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109.

Martin et al. (1988). Developmental stages of human brain: an MR study. Journal of Computer Assisted Tomography, 12, 917-922.

Noebels, J.L. (1989). Introduction to structure-function relationships in the developing brain In P. Kellaway & J.L.Noebels (Eds.), Problems and Concepts in developmental neurophysiology (pp. 151-160). Balitimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Renner, M.J. & Rosenzweig, M.R. (1987). Enriched and impoverished environments. New York: Springer.

Scherer, J. (1967). Electrophysiological aspects of cortical development. Progress in Brain Research, 22, 48-489.

Schore, A. N. (2016) Affect Regulation and the Origin of the Self. New York: Taylor and Francis..

Sur M, Rubenstein JLR. (2005) Patterning and plasticity of the cerebral cortex. Science.310, 805–810.