Purpose isn't just some grandiose, once-in-a-lifetime discovery. It's not a single "aha" moment where suddenly everything clicks.

Instead, we can view a sense of purpose as an ongoing narrative that evolves with our unique sensitivities* and experiences - and the meaning we make about those sensitivities and experiences.

*a sensitivity is related to what we notice in our external and internal environments. What do we seem to notice that many others don’t?

The following are 5 keys that emerge from systems-thinking and neuroscience research as it relates to Purpose

Listen to this episode on:

#1 - PURPOSE ISN’T ALWAYS A GRANDIOSE THING

A sense of purpose can be something that lights us up and motivates us to strive to contribute something unique and special.

But... as we'll see from the research...

purpose can also be about understanding that we are all playing a part of bigger, interconnected systems.

Our sense of purpose is tied to the systems around us—our families, communities, even the universe—and understanding how we fit into these complex, interconnected webs.

From the neurons firing in your brain to the city, family and community you live in, everything operates as a system. By viewing ourselves as part of these systems, our brain activity opens up to new types of connectivity. We start to see patterns, connections, and roles that we can play.

#2 - BRAIN CONNECTIONS IMPROVE WHEN WE THINK OF OUR INTERCONNECTEDNESS

Brain research shows higher connectivity of important brain networks in people who see the world from a larger, systems view

What research points to is that this kind of systems approach to narratives also activate particular networks in the brain that help us become more agile, and more adaptive.

Systems-related purpose is tied to a shift in perspective.

It’s about going beyond the "here-and-now" (or "there-and-then"), and creating abstract narratives that reflect broader systems, processes, and contexts.

It’s about connecting dots that transcend what is directly observable in a situation.

Here is an example* that illustrates the difference:

We see two people cutting stones.

- One of them describes their purpose or function by saying ‘my purpose is to cut stone’ . That would be A concrete, here-and-now description.

- In contrast, the other person says ‘I am building a place for community to gather’. This goes beyond the here and now and begins an abstract projection of what a larger system that their actions are contributing to.

*from the Open University course on Managing Complexity

New, pioneering brain research is looking at how this kind of narrative building wires the brain and improves life outcomes.

In particular, work by Mary Helen Immordino-yang and colleagues, is looking at the long-term effects of purpose and transcendent narratives in terms of mental health, relationship skills and academic performance in adolescents.

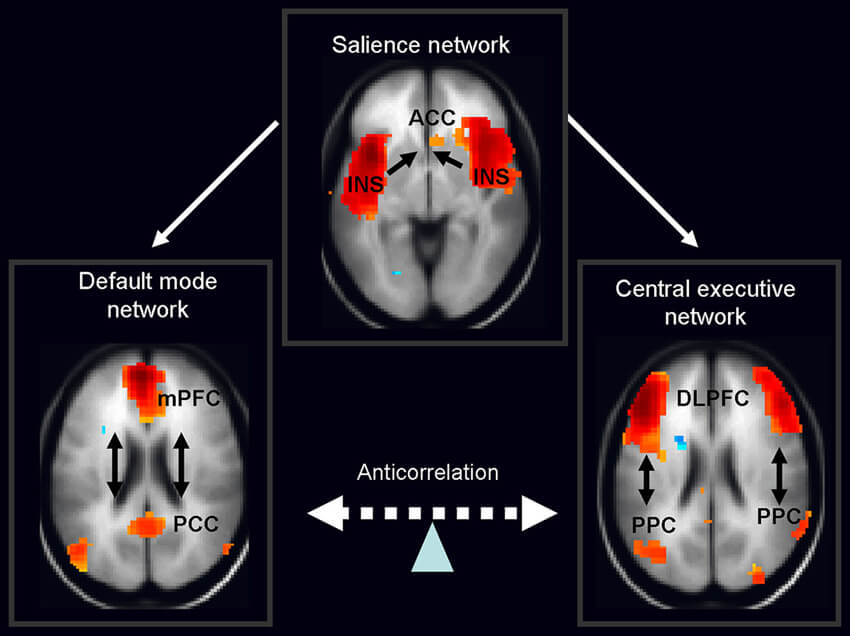

Their research points to three main components of narrative-building, supported by three of the brain's major networks: affective salience, effortful attending, and broader reflection:

- Affective recognition: aka., feel the emotional 'juice' of why an issue is important (Salience Network).

- Use the emotional juice to build skills and information related to the issue (Executive Control Network); and

- Connect the work to big ideas that are related to systems and processes in the world (Coordinated connectivity between the ECN and the Default Mode Network).

#3 - THREE BRAIN SYSTEMS ARE SHOWN TO CONNECT MORE DEEPLY WHEN WE ENGAGE IN SYSTEMS- AND PURPOSE-THINKING

These networks include the Salience Network, The Executive Control Network and Default Mode Network

The Salience Network (SN). The SN weighs the relevance and perceived importance and urgency of information to motivate further thinking. Think of emotional engagement and the SN like a motor that both pushes our thinking and steers it.

The Executive Control Network (ECN) helps us pay attention, hold information in mind, shift strategies, and focus on goals. It also helps us ignore distractions, regulate emotions, and control impulses.

The Default Mode Network (DMN): the DMN activates when we build abstract narratives that reflect broader values and systems-level explanations. The DMN is activated when we reflect, imagine hypothetical or possible future scenarios, remember the past, and process morally relevant information. It's important for creativity, nonlinear and "out-of-the-box" thinking, for constructing a sense of self, and for feeling inspired (Immordino-Yang, 2016).

#4 - ABSTRACT, TRANSCENDENT NARRATIVES ARE TIED TO ACHIEVEMENT AND SELF-ACTUALIZATION

The studies showed that students who used abstract, transcendent and system-based narratives in their explanations showed, in the long-term, higher levels of academic achievement and self-actualization.

Their narratives reflected what the researchers call dispositions of mind - these include 3 key tendencies to :

- engage reflectively with issues and ideas,

- be curious and compassionate, and

- use what they learn to inform their emerging values.

Years later, the network that supports self- directed and regulated behavior and emotion, and the network that supports reflective, big- idea thinking, were better coordinated in teens whose narratives had been not just concrete, but also abstract.

This coordination between ECN and DMN, in turn, predicted better personal and scholarly outcomes in young adulthood.

#5- IT GOES BEYOND IQ AND SOCIOECONOMIC STATUS

These findings held above and beyond the predictive power of metrics like IQ and family socioeconomic status.

This suggests something really important:

that there is something more foundational about what is happening inside the brain...

Something that taps into something deeper than a person’s circumstances.

As a repeat, the subtle distinctions they saw were between:

- concrete narratives about emotions, actions, and consequences of the "here-and-now" (or "there-and-then"), and

- abstract narratives that reflect on the broader systems, processes, and contexts that transcend what we can directly observe in a situation.

It's not enough to just have an emotional response, or to repeat words to show interest or empathy. To benefit from these positive effects over time, the brain needs to engage in emotionally driven work of deep thinking for oneself.

Research suggests that although the difference between here-and-now versus transcendent, systems-oriented thinking is subtle, they are critical for psychological growth, social-emotional well-being, and for the brain.

As the researchers assert, here-and-now thinking doesn’t reflect an awareness of the bigger picture or the broader historical or cultural systems that interconnect with human behavior. Systems-oriented, transcendent type of thinking reflects complex personal and community histories and cycles that can influence people’s actions and what they believe.

PURPOSE-FILLED REFLECTIONS

Purpose isn't just about grandiose ideas or visionary goals.

It's also about our the story we tell in terms of the role we play in the larger interconnected systems we are a part of.

- Are you acting purposefully, with intention and awareness?

- Do you see yourself as playing a role in multiple interconnected systems?

- Do you reflect on how interconnected systems play a role in others behavior?

Tuning into a sense of purpose means being open to learning and adapting, rather than a concrete roadmap.

It's a flexible, evolving narrative that you build as you gather more data, experiences and inputs, and then tie them into the larger systems you are a part of.

References

Gotlieb, R.J.M., Yang, XF. & Immordino-Yang, M.H. Diverse adolescents’ transcendent thinking predicts young adult psychosocial outcomes via brain network development. Sci Rep 14, 6254 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-56800-0

Haghighat, H., Mirzarezaee, M., Araabi, B. N., & Khadem, A. (2021). Functional Networks Abnormalities in Autism Spectrum Disorder: Age-Related Hypo and Hyper Connectivity. Brain topography, 34(3), 306–322. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10548-021-00831-7

Immordino-Yang, M. H. (2016). Emotion, Sociality, and the Brain’s Default Mode Network: Insights for Educational Practice and Policy. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 3(2), 211-219. https://doi.org/10.1177/2372732216656869

Immordino-Yang, M. H., Christodoulou, J. A., & Singh, V. (2012). Rest Is Not Idleness: Implications of the Brain's Default Mode for Human Development and Education. Perspectives on psychological science : a journal of the Association for Psychological Science, 7(4), 352–364. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691612447308

New program coming October 2025

Early bird discount ends July 31st (with immediate access to online bonus material )