Fear is not a bad thing.

Just like anger and sadness, emotions are windows into different patterns of beliefs, unconscious triggers and thoughts about ourselves and others.

When we let ourselves NOTICE our feelings, we have a better chance of choosing if we want to keep feeling that way.

We can make the unconscious conscious.

When we numb ourselves or deny our feelings, we don't get a chance to explore their patterns.

Fear is necessary for keeping us alive.

Unfortunately, because humans live in a very metaphorical and symbol-based reality (using 'sophisticated grunting' as language, and words as symbols), our fear system can sometimes make us predict and group things/people/situations as more dangerous - and therefore worthy of elimination or avoidance than they need to be.

That's when we might want to ask ourselves:

- do we want fear to move our brain into its most primitive, repetitive reflexes...

or...

- do we want to help our brain use its most sophisticated, nuanced and adaptive systems to help us navigate a way forward. Is that what we want?

Here are 3 key things to know about why fear plays such a part in our life and how it affects us.

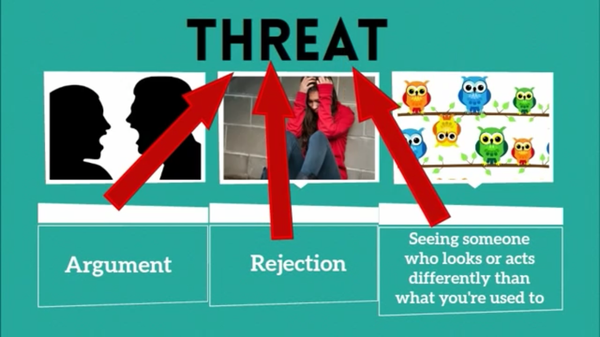

#1: Fear is generally the default reaction to something our mind-brain-body perceives that we can’t control or understand.

This is because we have a higher chance of surviving if we detect 'false positives' rather than false negatives.

Another way to say this is that when our system automatically puts something unfamiliar in the 'danger' category, if it's correct - great! That just saved our lives.

If it's wrong, 'oh well' - we might miss out on something that could be beneficial, but the cost of our system assuming the worst is worth it because it keeps us alive (technically speaking, from a brain-based statistics perspective).

This means that there is a higher chance that most of us miss out on new experiences because our mind-brain-body system places things we don't understand into the 'threat' category.

Some of the things we miss out on can include:

- meeting people who are very different than us

- listening deeply to try to understand opinions that are different than what we hear all the time

- allowing ourselves to feel feelings that we don’t understand

- having an experience that could change our life, even if it could end up in rejection (like public speaking, auditioning for something)

If we don’t build a track record of experiencing these kinds of things, our system doesn’t have any new ‘data’ to predict the probability of surviving those experiences.

So we end up just ‘sticking to what we know’.

The more we interact only with people and situations we are familiar with (including online), the bigger and more generic the category of ‘danger’ becomes.

The world becomes binary: a small number of familiar people are ‘safe’ and massive amounts of unfamiliar people and experiences are ‘unsafe’.

This makes the world a very stressful place!

# 2: We tend to over-generalize fear

"brains do not react to the world, but instead predict and then test their hypotheses against incoming sensory evidence."

-Feldman Barrett et al., (2016)

Because our mind-brain-body system is an efficiency machine, it also does us the "favor" of grouping things together so we don't have to analyze each and every person and situation.

If we've had one negative experience with something, many neural resources are devoted to making sure we don't repeat whatever that was.

This can happen for things like getting food poisoning from eating oysters and never wanting to eat them again even though each oyster is not necessarily going to give us food poisoning.

This can also happen for things like if we experienced a parent or caregiver as threatening, our brain may pick up on something from a boss, or romantic partner or someone who has features that our brain associates with whatever that is with our past negative experiences.

It then puts us into a defensive mode without us even realizing it.

This can be called a 'schema' (Ledoux, 2019) and can also be referred to as predictive coding, active inference or belief propagation accounts of brain function (see references); and aligns with our understanding of the brain as an energy-regulating predictive processor.

"Fear can even occur when some or all of the subcortically triggered consequences are absent: when the threat alone generates memory-based expectations that mentally simulate the missing elements, thereby pattern-completing your fear schema Ledoux 2015)

(see also Lang's Fear Network model and Emotional Processing theory in this paper from Harvard as well as a set of wonderful papers by the Royal Society on Interoception and mental health: find them in the references section).

And this can happen when we dislike the opinion of one person.

Our brain will try to be efficient by putting that person into a category, so we can just avoid (or attack) that category altogether.

From a brain- perspective, over-generalizing** is much more efficient than actually trying to understand and getting to know every single person we interact with.

**In fact, some of Carol Dweck's original research was on the use of 'generic language': as children, around 40% of the language we get about the world is 'generic', meaning pluralized and categorized, rather than individuated. Example, "cats are ___, adults are ____". This can lead a child to believe certain traits are innate about a group, rather than see them as individuals. (see Navigating the Social World for more on this).

#3 We ‘learn fear’ from other people.

This means we don’t even need to have a direct experience with something to be afraid of it.

We just need to be around someone else who is afraid of it (especially if we trust that person). Their reaction will create biofeedback signals that we then detect and associate with whatever they are afraid of.

(An example of this would be a child being afraid of a bee or spider even though they’ve never been hurt by one, but they have seen a parent get freaked out.)

What do all three points have in common?

They show us that:

Many of us are afraid and defensive more often than we realize.

So how do we get around this?

Fear is extremely easy to learn and extremely difficult to unlearn.**

We can’t expect ourselves to ‘unlearn fear’ naturally.

But we can train features of the brain to come online more quickly in response to our fears so that if whatever it is ' doesn't kill us, it makes us stronger'.

**Read more about this in Joseph LeDoux's research and Robert Sapolsky's book, Behave: the Biology of Humans at their Best and Worst

Here’s one way to train your brain to have more access to its higher order features:

Beware of your 'fastest reaction'.

Your survival mechanisms will always be the first to take over.

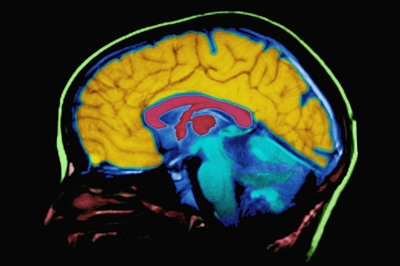

Signals coming from our five senses and our internal organs need to travel from our spinal cord, brainstem, limbic system, until they finally reach the areas furthest away from our spinal cord - the prefrontal cortex. This means that signals take longer to reach the more evolved areas of our brain.

Sophisticated, more deliberate responses use more energy than our more primitive reflexes.*

The prefrontal cortex plays a major role in being the ‘control tower’ of the brain. It has a lot of coordinating and processing to do. It is designed for more complex functions and calculations, rather than reflexes.

*see this Geary D. C. (2021) paper on mitochondrial functioning (see references below)

Your 'fastest' reaction will keep you alive when something is an actual threat.

(so we don't want to get rid of this system)

BUT... for ‘non-life-threatening’ situations, such as conversations, online behavior… situations where our life is not actually in danger...

it may be worth honoring the micro-moments it takes for our more thoughtful brain features to catch up.

When you are engaging in an angry/upset text, phone conversation or social media post:

the faster you are typing and replying, the less likely this is coming from your more evolved neural architecture.

The more you are able to slow the pace down, pause, take some breaths, move away and come back again (after you've engaged in other types of conversations, movement, nature, gratitude, silence), the more you are giving your higher order brain a chance to keep up, process, and then come up with something that is more intelligent than what your primitive systems will get you to do.

Take a moment before you move a muscle (this includes speaking and typing muscles!)

to let more signals travel to your higher order brain areas.

Breathing deeply also engages the vagus nerve, which can dampen the sympathetic nervous system (mobilization mode), and open up blood flow to neural resources for communication and flexible problem-solving.

If we keep having the same types of arguments or interactions-without-new-ways-forward (either in our head, online or in person), it means we are ‘re-acting’*.

*Reacting: to re-act. To act again and again in the same way.

We will keep acting out the same dramas until we break the cycle.

This relates to us personally, in our families and collectively as a species.

If we don't want to see history continue to repeat itself, we have to override our own default defense systems.

It starts on an individual level first.

It's easier for us to blame a bigger system or group of people. This is related to 'shifting the burden'... Our brains like conserving energy - making someone else responsible alleviates the energy-burden in that moment.

It's not that we shouldn't take larger systems into account - they are a part of our reactions and functioning. But to access our most powerful neural and behavioral resources, we need to start internally first.

As cliche as it sounds, we start with ourselves... we watch what happens as we notice and shift our micro-movements. We allow our Inner Intelligence to offer new pathways and insights.. and then... we can turn more of our focus to others and to larger systems.

If we move our focus to others and larger systems FIRST.. we miss out on the very mechanisms that is making them act the way they act.

Each interaction and system is made up of individual humans and brains that are in modes of reflex, fear and predictive processing. If we can't figure out how to open up new ways of responding within ourselves.. how can we attempt to model/explain/persuade and influence others and larger systems?

It's an inward to outward process.

The more effortful - and therefore sophisticated-brain-building - choice is to reflect on our OWN reactions.

Those small moments of irritation and impatience, with loved ones or strangers.

How do we create a NOTICE-PAUSE-SHIFT sequence?

- notice how fast you are speaking, typing or moving

- pause to allow new signals and systems to activate in your brain-body

- shift your focus into slowing down your eyeball movement, breathing, talking, typing and/or moving.

and then... notice if any new idea, perspective or insight happens. See what type of Inner Intelligence starts to emerge. It may sound like a much wiser inner voice or presence.

There is a deep, sophisticated intelligence that has the potential to emerge in every human - we all have collective information from our experiences that can contribute to a New Way forward.

But we must use effort and intention to override our more primitive reflexes.

There is no other option. It won't happen easily and effortlessly.

The beauty is that effort is where the 'juice' is.. things that initially take effort eventually flow with more ease.

Awkwardness and effort are signs that the brain is leveling up. It's shifting its energy to help you do something new.

And that leveling up is where our most empowering, most intelligent state of being exists.

On that note, let me leave you with the words of someone who clearly allowed his prefrontal cortex to come online in the face of fear.

(if you haven't read Long Walk to Freedom, I highly recommend it)

If you know of anyone who could use these words, please share this article with them...

*notes on vocabulary:

Brain: I prefer using mind-brain-body instead of ‘brain’ because it is a complex system that includes the electromagnetic fields surrounding and pulsing through the body + feedback loops carrying intelligence from cells (especially the cellular membranes), visceral organs (especially the heart) to the brain and from the brain back to the organs and muscles + a ‘social mind’ that includes the data created by signals we exchange with others. If I do use ‘brain’, I mean the mind-brain-body system.

Familiar: its origin includes 'belonging to a family', which I love: when we attempt to get to know someone or something, we are making them ‘familiar’. We are making them a part of our family.

References

Clark A. 2013 Whatever next? Predictive brains, situated agents, and the future of cognitive science. Behav. Brain Sci. 36, 281–253. (http://doi:10.1017/S0140525X12002919)

Deneve S, Jardri R. 2016 Circular inference: mistaken belief, misplaced trust. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 11, 40–48. (doi:10.1016/j.cobeha.2016.04.001)

Barrett Lisa Feldman, Quigley Karen S. and Hamilton Paul (2016) An active inference theory of allostasis and interoception in depression. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B37120160011 http://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2016.0011

Friston K. 2010 The free-energy principle: a unified brain theory? Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 11, 127–138. (doi:10.1038/nrn2787)

Geary D. C. (2021). Mitochondrial Functioning and the Relations among Health, Cognition, and Aging: Where Cell Biology Meets Cognitive Science. International journal of molecular sciences, 22(7), 3562. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22073562

Hohwy J. 2013 The predictive mind. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Larkum M. 2013 A cellular mechanism for cortical associations: an organizing principle for the cerebral cortex. Trends Neurosci. 36, 141–151. (doi:10.1016/j.tins.2012.11.006

LeDoux, J.E. Anxious: Using the Brain to Understand and Treat Fear and Anxiety. (Viking, 2015).

LeDoux and Mobbs, D., Adolphs, R., Fanselow, M.S. et al. Viewpoints: Approaches to defining and investigating fear. Nat Neurosci 22, 1205–1216 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-019-0456-6

Mumford D. 1991 On the computational architecture of the neocortex. I. The role of the thalamo-cortical loop. Biol. Cybern. 65, 135–145. (doi:10.1007/BF00202389)

Mumford D. 1992 On the computational architecture of the neocortex. Biol. Cybern. 66, 241–251. (doi:10.1007/BF00198477)

Join us for this Incredible Global Event of Neuroscience and Thought Leadership

These coaches, leaders and educators are modeling and teaching how to integrate self-regulation, systems thinking, resilience and adaptability as forces for growth and personal evolution.

If you’re ready to dive deeper into these ideas, I invite you to check out the Super Regulators Master Class on self-regulation, systems thinking, complexity, and growth mindset.